Composing

Welcome to the information page about Composing Music.

Composing Music is a first on the list of things to do, or learn. Although modern music allows crossing the borders between Composing, Recording, Mixing and Mastering. Composing is a good starting point when you newly play an instrument or you are just starting to get interested in music making. On the upside there is a lot information around and known about chords, notes, scales and structure. The downside is that this information is almost all reading and understanding, it can be experienced as uplifting or some find it very boring. Sometimes it will be difficult to understand when you read about technical things about music. Just because music is worldwide played and enjoyed, you can find information on the internet about ways to learn music, lessons and opinions. Maybe you will be overblown by all this info. On this page we try to give you an overview what is available and what is important to know when composing a song or track, or learning to play an instrument. On the other hand this SINED site is off course only one of the many sites about music.

AAMS Auto Audio Mastering System

Improvisation

Improvisation is the practice of acting and reacting, of making and creating, in the moment and in response to the stimulus of one's immediate environment. This can result in the invention of new thought patterns, new practices, new structures or symbols, and/or new ways to act. This invention cycle occurs most effectively when the practitioner has a thorough intuitive and/or technical understanding of the necessary skills and concerns within the improvised domain. To me, it is important to stay with an improvising mind. Whenever you’re playing an instrument of any kind, you can always relax and enjoy your instrument. So a lot of people starting will be advised to read notes and scores, learn to play them and learning a lot of technical stuff about music. That will be helping making you understand music more, it is not the only way to do so. Keep in mind that just playing your instrument out of your head exploring the possibilities, relaxing, improvising and goofing around is just as supported and commonly accepted as a part of music making. Some people do not want to learn all this technical stuff, some do. It is all up to you if you do everything by the book or not. And now days there are a lot of artists and recordings around that were made by people who never even could read a single note out of a score. They are just bashing tunes out of their instrument or equipment and are having a blast doing it. They are successful with their way of doing things, their style of making music. Experienced players who are theoretical and well educated, who know to read and play all sorts of scores, scales, chords, etc, maybe good at reproducing music that has already been made. Maybe they will not be as good in composing music or playing their instrument in an improvised session. Maybe someone will tell you that you are playing wrong chords or notes, because technically it is done in a structured way. Maybe someone will tell you that reading scores and knowing chords, scales is the most important thing to learn playing an instrument, well then it is good to know you are never doing anything wrong or right. Music is an open format; you can do anything you like. If you will be successful or not, it depends what you are looking for in Music Making. This will be you deciding what is important for you to learn or not. Investing in time and relaxing with the whole subject is a good thing to do. Watch and learn from other people, never be afraid that they might be better and more educated. If music becomes a fight to be the best and making you win the game, this will not help when you are not relaxed playing music. Just understand that everything you learn takes time to be processed by your brains, playing and repeating learn, investing time and patience is best. Playing an instrument means practicing a lot, knowing your instrument. Also teaching yourself that improvisation is just as important. Just remember not to get hasty and relax, take your time to explore what you’re doing. To me there are two kinds of players, some can improvise and some just play what has been given to them. Ok you can learn notes, chords, scales and every score you can find, you will get better playing your instrument and you will get better at learning overall music. But this will only go for music that has already been made and written, it’s good to learn from others. But it does not really help you improvising and inventing new. Mainly for composing or making music, improvisation is a key element. In a beginning rock band you might find 4 or 5 players. Most likely not all players are in the process of composing the music for the band. Most members of the band will be only playing what has been given to them by the other band members who compose or write the music. It is likely because of communication and band structure that only 1 or 2 players actually are getting involved with the composition of songs, they write almost all music for the other band members. The other players never get so much involved in composing the material they play, because this might be lack of improvisation on their part or just band structure agreement, who is running the show. Some players are just happy to just play that has already been written. Some players have learned so much about what has already been written, they know their chords and progressions, because they have learned them by the book. It’s ok, but it might keep them from inspiration, improvising and invention.

Improvising, Inspiration and invention are needed to create!

The creative side of music is the most comprehensive and rewarding thing once you get the hang of it. Learn yourself that although doing things by the book, does not mean that you will be best off. It means you are educated, it is proven ground. You can learn from what other people do and have done in the past. Remember that people are creative by themselves. You can create new melodies and chord progressions, you can learn by improvising and you will re-invent yourself while doing it, exploring the unproven ground. Composing and Making Music is getting inspiration, improvising and invention from others or you reach into yourself to get it out. So if you are playing or making music, just understand that time is the main factor. Dividing time into learning and goofing around (improvising) is important. Once you have invested time playing and improvising your way, you will be more educated by yourself and how you like to play your instrument or equipment. Learning is time consuming, take your time and do not get frustrated by overdoing the practice. Your mind most be settled down and you most understand what you’re doing, this might take more time then you think it will be. Rushing things is never good. It is good to know there are always people better (or worse) then you make up your own mind in these situations. Learn from it, instead of competing. Players who compete with other players is a good thing, but over competing is not. Music is a set of instruments that each play their part of the whole. This means that competition is not a factor in written music, getting the best out of it is the way to go. If this means sacrificing yourself to have more room for inspiration and improvising, that will be a good thing. Making and creating music is by itself easy. Sit down and play. But for newcomers the vast available information might get them off-track, they are egar to grab hold of any information or learning process. There is a good chance you will be advised to learn all kinds of stuff and you will be over educated. There is a chance that by learning by the book, you will only play by the book. The more time you spend on playing by the book, the more chance there is you will get stuck by being thought structured and you might be hanging onto what other people have done before. Remember music is more free then that and there is more success to be made with the basics, making things complicated is most likely not the way to do music. Once your improvisation has resulted in new music or compositions, you will get inspired even more with the results.

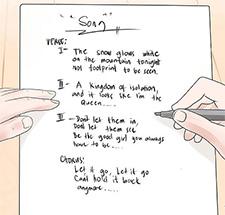

Step 1: Writing a Song

Without a song, how could one possibly begin to record. Typically, writing a song starts with an idea or an inspiration. It may begin with lyric and a melody, a chord progression, a unique sound/loop or an improvisation that takes on a life of its own. Once this idea has developed enough to stand on its own merits, the music production process can then begin. A music production must support, in every way possible, the message or prevailing emotion of the song. The most common mistake I see today with young producers and songwriters is that they focus on the sounds or production elements before the song is finished being written. For certain styles of music this can work if the production invokes a feeling or emotion that inspires the lyric and melody. In many cases though, the production sounds disjointed because the lyric and melody end up being limited to the production style or arrangement. What happens next is that the arrangement must be adapted to the lyric and melody and the production can easily lose the coherency necessary for the song to carry its message.

Traditional Songwriting

Traditionally, writing a song is done with a singular instrument, a lyric and a melody. That's why so many songs start out as a piano and vocal or acoustic guitar and vocal. If you were writing a song with a group of musicians, they would likely become bored or disinterested if you spend too much time experimenting with melodies or new lyrics. When writing a song, it is typically best to work through these issues alone or with a writing partner that will help you quickly dismiss ideas that just don't work. Once you have flushed out all of these issues the music production process can really begin in earnest. When carefully crafted, a song will hold the interest of the listener. A song tells a story that conveys ideas and emotions. If the story is something the listener can relate to then they will listen as long as it is told in a compelling way. Great storytellers are very dynamic and interesting people as are great recording artists. They convey the emotions and events in a song with vivid imagery that takes you on a journey. Although the recording artist and the songwriter are not always the same person, the pairing of artist and songwriter is critical to the success of a song. Sometimes they work together in the process of writing a song so that the artist can add their input and perspective of what the song is about. If the artist cannot relate to the song from their own personal experience, then it will typically sound hollow. The passion must be there for the song to be taken in by the listener.

Modern Songwriting

The blessing of the process for writing a song today is that there are so many resources available, you don't need a band to make a music production. You can create a template production that allows you to work on your ideas without wearing other people out by making them play the same parts over and over again. The use of music loops and samples is an exceptional way of getting the creative juices flowing and setting the stage for writing a song that's inspired. This process can also have pitfalls. One of the most common is that the songwriter may fall into the trap of focusing on the production elements instead of just writing a song. Without a good sense of judgment, the songwriter may ignore the real problems which may be that the lyric or the melody just isn't very good. By focusing on the production elements they may waste hours, days weeks or months trying to salvage a song that is not really ready for the music production process. It is for this reason that I believe most of these tools are best used in the demo stage of the music production process. I've seen too many songwriters lose their flow while writing a song because they spend hours trying to work out technical issues instead of just writing. Keep the songwriting process simple. Always have a recording device with you to capture an inspired idea. If you have a smart phone, your one app away from having a portable recording device with you at all times. For those that struggle with writing a song, good lyrics and melodies or finding good subject matter to write about, there are many websites and forums on songwriting to hone those skills. Writing a song is an art form in itself. However, to start the music production process, the quality of the song cannot be ignored. If you want to become a music producer, you cannot ignore good songwriting skills as a necessary part of your repertoire. The ability to assess issues and make necessary corrections will go a long way to helping you be successful. It is the song, after all, that the listener will relate to most, not the production. To be very clear, the process I have been talking about here is all about songs that are meant to be the center of one’s attention. Although many of the ideas presented here will also work for other forms of music, the focus here is on lyric driven music. Since all music carries some story or emotionally driven feeling, the concepts here can be adapted to the production style to achieve similar results. A jazz or classical record, for example, also convey emotions that tell a story. Even though the story may not be as explicit as a lyric driven song, the same process can be used to aid the listener into the interpretation of that story.

Basic Principles of Writing a Song

To help lend a broader understanding of writing a song, let's go over some of the key elements of good songwriting and how they affect the music production decisions you make. These four basic points of focus must be addressed before the song enters the recording phase of the music production process. What the hell is your song about? What feeling are you attempting to convey? Love, jealousy, hate, anger, fun, etc… These decisions lay the groundwork for EVERY other decision that is made including what sounds and instruments are selected in the production process. Writing a song about heroin addiction, for example, is not going to have bright tinkling bells as part of the music production. In this example, the musical elements of the song will need to be dark and oppressive sounding so that they support the prevailing message of the song which is most likely about depression and helplessness. Conversely, writing a song that's meant to make people party and dance is not going to be filled with dark heavy depressing sounds. The elements used here will be brighter, punchy and focussed. They will need to pump and breathe at the pace a person would dance to. While this may seem obvious on the surface, the real artistry of writing this type of music is doing something unique while remaining within these parameters.

Telling the Story

How do you plan to convey this message? These decisions all start with the prevailing message or feeling from the song. This can be as simple and using a minor key for a sad song versus a major key when the message is more positive. The blend of melody and lyric must support each other in every way. If the prevailing message is one of irony or sarcasm, writing depressing lyrics in a major key could convey a sense of humor or show a person trying to cover up their true feelings about the subject matter. There is no way to underestimate the importance of this relationship. The human brain is wired to receive and process information in a very particular way, if you go too far outside of these parameters, the message will be lost on most that care to listen. When presented well, you open a doorway to the listener's consciousness. From there it is up to you to keep the door open by continuing to hold the interest of the listener. Of all the topics surrounding the music production process, this is the one with the least number of technical solutions. No plugin, compressor or effect will cover up a bad song for very long. No processor will change the attitude or feeling of a song. These tools can only enhance an energy that must already be present. In the example above, heavily compressing the recording may help to convey the feeling of being trapped. This approach may work against you, however, if the song focusses on the feeling of freedom while on the high. This is the reason that the songwriting process is so critical to get right before even attempting to start to make a music production out of it. If a song can't hold the interest of a listener when presented in its most simple form, then it likely can't withstand the music production process without becoming and endless parade of band aids.

Holding the Attention of the Listener

How would you like to present the song? How will the dynamic energy of the song flow? Do you want it to start out simple and end big? Do you want it to start out big, drop down in energy and then explode in the end? Do you want it to maintain an even energy level throughout? Any one of these methods can work if the selected method supports the message of the song. The classic structure for a song starts with a verse which presents a story or situation. It tells you what happened, how you got into this situation in the first place. The chorus section then conveys the emotional result of the story that has just been told. It tells the listener what has resulted from the events told in the verse. Usually, there is a back and forth profession between verse and chorus that may lead into a breakdown or bridge section. The breakdown or bridge sections will take you to another perspective of the story. It may be the truth of what has transpired, it may represent a reprieve from the story so that the impact of the remaining story is more dynamically felt when the next chapter is told. This traditional method of songwriting is not necessary if a creative way to keep the interest of a listener is created. A song about the repetitive nature of living and working in a big city may benefit from a repetitive loop or programmed rhythm. The programed, repetitive nature of the production may help to convey the feeling of living a robotic life, repeating the same pattern of living day after day. The reason why the traditional verse, chorus, bridge method works is that there is a template that will most likely to hold the interest of the listener if presented well. Every story has a setup (verse) a problem or dilemma (chorus), a realization or solution (bridge or breakdown), and an ending. The ending can be any of the other song elements or something completely different depending on how the story ends. A song is basically a 3-5 minute movie in audio form. I like to use visual references when talking about any kind of audio because the reality is that sound is a secondary sense to sight. Up until the age of synthesis, every sound that we ever heard came from a physical object that we could visualize. This programming has been built into us for thousands of years and serves us well as a survival mechanism. Sound allows us to perceive and interpret things we may not be able to see. Sometimes they are dangerous things, like a car racing through an intersection you are about to cross. Sounds presented well in musical form also help to support or create the images or feelings that are presented in the song. A song is no different than any other form of audio. A song can create images in a person’s mind. They listener may recall past events in their life that relate to the story being told in the song. The music production helps to support that imagery. When properly done it may bring a person back to their own personal experiences that they can remember and relive through your song.

Feeling Over Thinking

When a song is well written the dynamic of the song will be clearly spelled out by the story. It will help you decide if you should use a breakdown section instead of a bridge section. It will help you decide whether to fade out on chorus sections, a vamp section, end the song with big crash or just a simple melody. Unless you are writing a song that is meditation music or attempting to put the listener into some kind of hypnotic state, people will respond most to differences in things, not sameness. Without this progression of dynamic changes, people will get bored and turn you off. The best way to judge whether a song is ready for the music production process is to FEEL it instead of listening to it. In other words, stop thinking and just let it speak to you. Pay close attention to any section of the song where you lose interest or feel your attention is taken somewhere else. Does the song hold your full attention from beginning to the end? Does it drag on too long? Do you feel cheated of shortchanged by the song because it is too short? Do you feel satisfied after listening to it ? Remember, feeling will always outweigh thinking! If you find yourself trying to convince somebody why a song is good, then you should already know that something is wrong. If you have completely lost your perspective, shelve the song for a while until you can listen with fresh ears. Listening to the same thing over and over can have the effect of burning it into your consciousness. You lose the ability to be objective. Finally, when writing a song, never ask somebody what they think of it. Unless they are a professional producer or artist and are brutally honest people, they will usually BS you because they are your friend and trying to support you. The best way to judge a song is to play it in the background and just watch for reactions without soliciting one. Do they move their head or body to the beat? Do they leave the room singing the lyric or melody? Do they ask you about whose song this is? These are clear signs that something is right because they are feeling it, not listening to it. You may want sometimes to write down some melodies or chords.

Using symbols C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B for writing down notes can be helpful when you need to capture melodies, baselines, etc.

Using common chords symbols like C, Cm, Am, or D can be handy to write down chords. Also for chords it can be handy to store how many times the chord is played. Using C/ Am/ E/ C for wiring down your chord list might not be enough. So you can write C/ Am / E (2/ 2/ 4), this means the C chord is played 2 times, the Am chord is played 2 times, the E chord is player 4 times. You can safely say that (2/2/4) is the same as (4/4) , but at least you can write down what your intending to do with the chords, take in account of how many times a chord is played inside bars. Anyway it is important to have a system for writing down notes, chords for melodies and composition. I do not use any scores for writing down, scoring is a better way of doing things, but it can be more complicated to learn and more time consuming.

Keyboard Playing

Playing on midi keyboards is a common thing, now days music making on a single computer can stand with one single keyboard for inputting notes and chords. When you are new to playing a keyboard we will first explain how it works while composing music.

Note C.

You can see we will start basic with the note C.

Octaves 1 to 5.

On this keyboard there are 5 octaves and the C note can be played five times from C1 to C5.

Notes C, C#, D, D#, E , F , F#, G, G#, A , A# and B.

Let’s investigate one of the octaves. The white notes labels are C, D, E, F, G, A, B. The black notes labels are C#, D#, F#, G#, A#. Together they form one octave.

Major Chords.

Now here is where it is getting interesting, to remember all Major Chords, remember the sequence 1-4-3!

The Cmajor chord is played by pressing C, E and G together.

Minor Chords.

To remember all Minor Chords, remember the sequence 1-3-4!

The Cminor chord is played by pressing C, D#, G together.

Major Septime7 Chords.

To remember all MajorSeptime7 Chords, remember the sequence 1-3-4-3!

The CmajorSeptime7 chord is played by pressing C, E, G, A# together.

Major Kwint Chords.

To remember all MajorKwint Chords, remember the sequence 1-3-4-1!

The CmajorKwint chord is played by pressing C, E, G, G# together.

Just a quick overview:

Major Chords 1 - 4 - 3

Minor Chords 1 - 3 - 4

Major Septime7 1 - 4 - 3 - 3

Major Kwint 1 - 4 - 3 - 1

You may want sometimes to write down some melodies or chords.

Using symbols C, C#, D, D#, E, F, F#, G, G#, A, A#, B for writing down notes can be helpful when you need to capture melodies, baselines, etc. Using common chords symbols like C, Cm, Am, or D can be handy to write down chords. Also for chords it can be handy to store how many times the chord is played. Using C/ Am/ E/ C for wiring down your chord list might not be enough. So you can write C/ Am / E (2/ 2/ 4), this means the C chord is played 2 times, the Am chord is played 2 times, the E chord is player 4 times. You can safely say that (2/2/4) is the same as (4/4) , but at least you can write down what your intending to do with the chords, take in account of how many times a chord is played inside bars. Anyway it is important to have a system for writing down notes, chords for melodies and composition. I do not use any scores for writing down, scoring is a better way of doing things, but it can be more complicated to learn and more time consuming.

The Keyboard.

Advice for all computer and keyboard users is that a modern midi keyboard will be sufficient. But there are some traps to avoid. Get a midi keyboard that supports aftertouch and is touch sensitive. Cheaper keyboards do not support this kind of features, so really be sure you have these features on board. Touch sensitive playing. When you press a note on the keyboard, not only the note is send to the computer but also how fast and hard you are hitting it, this is most useful when playing natural instruments alike a piano. You can vary playing soft and hard, this is more expressive then playing a keyboard without Touch Sensitive keys.

Aftertouch.

Another things the Touch Sensitive keyboard can do, is when you are holding a note you can press softer or harder when to note progresses. For like Organ playing this can be a handy feature to control the effect of the rotary speaker. With Touch Sensitive Keys and Aftertouch you can at least input what your fingers are doing and record it more natural, both are highly recommended. It is likely when you do not need these features, when you do have them you can always turn them off. But you are at least sure that you’re getting the maximum out of your midi keyboard.

Pitch Control.

The place for pitch control on a keyboard is mostly on the left hand side, next to the keyboards lowest keys. Most common are wheels, joysticks and faders for this kind of operation. It is handy to have pitch control on your midi keyboard.

Modulation Control.

The place for modulation control on a keyboard is mostly on the left hand side, next to the keyboards lowest keys. Most common are wheels, joysticks and faders for this kind of operation. It is handy to have pitch control on your midi keyboard.

Other Controls.

Some midi keyboard do have touchpad’s and more wheels and faders for you to assign. For people using synths on a computer these can be handy to adjust parameters. But these can be done with the mouse or controller equipment, it is not as important as it can be fun. Most controlling on cheaper midi keyboard is quite good, but one you start to be a control freak maybe you will later look for more controlling options.

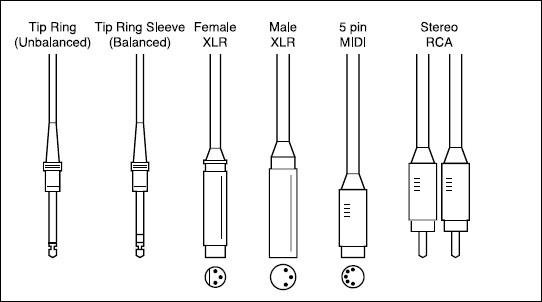

Midi or USB connections.

There has to be at least one Midi-Out to connect to the computer. This can be done using an USB-cable or midi cable. I still prefer the keyboard to be connected to a real midi cable, instead of using USB. So when there is a midi in and output on the keyboard or USB, choose midi to connect to your computer. Although USB is faster than midi, midi is more stable then USB. It is a matter of timing, when notes arrive to a computer. Until now USB is fast but can deliver notes that are just not the same as you played. Mainly a good written USB driver will help, but some manufacturers do better just then others by making USB drivers for their keyboard. Midi is proven, so connecting the midi cable to your computer is a good safe option.

Do Re Mi - Finding Chords

Minor 1 - 3 - 4

Major 1 - 4 - 3

Septime7 1 - 4 - 3 - 3

Kwint 1 - 4 - 3 - 1

White and Black Keys

The white keys are C, D, E ,F, G, A, Flats ' b' and sharps '#' are all black keys called

C#, D#,F#,G#,A#. The ' b' symbol can be used when ever needed.

One Octave are 12 notes in a row called C, C# or Db, D, D# or Eb, E, F, F# or Gb, G, G# or Ab, A, A# or Bb, B.

Major

Any time you see a letter on its own for example “F” this is called F Major or “F Maj”.

The Major Scale are seven notes in order 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 .

Root - Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

Do – Re – Mi – Far – So – La – Ti – Do

You choose a note or chord like C then count 4 notes up for E and 3 notes up for G, so C, E, G make up for Cmajor or just talking chords C.

Major = 1 - 4 - 3

Key Root 2n d 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th

Cm c d e f g a b

Gm g a b c d e F#

Dm d e f# g a b c#

Am a b c# d e f# g#

Em e f# g # a b c# d#

F# F#/Gb G#/Ab A#/Bb B/Cb C#/Db D#/Eb E#/F

Db-m Db Eb F Gb Ab Bb C

Ab-m Ab Bb C Db Eb F G

Eb-m Eb F G Ab Bb c d

Bb-m Bb C D Eb F G A

F-m F G A Bb C D E

Minor

Every major key has a corresponding relative minor key. You choose a note or chord like C then count 3 notes up for D# and 4 notes up for G. So C, D#, G make up for Cm.

Minor = Notes 1 - 3 - 4

The minor key will be in the same key signature, and will contain the same notes as the major key. The only difference between the two is that the minor key simply starts on a different note. In the key of C Major, the relevant, corresponding minor key is A minor.

You can always find the relative minor key by counting up six notes from the root of the Major key. So in the C Major example: C, D, E, F, G, ->A<-, B, C.. The minor key starts on A.

Root – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone –Semitone – Tone - Tone

So if as an example we use the A minor scale which is the relative minor scale of C Major, we have the following sequence of notes:

A B C D E F G A

If we were playing in F Major, the relative minor would again begin on the sixth note in the key, which would be the D, and the sequence of notes would be:

D E F G A Bb C D

Minor.

If you see "Fm" or "Fmin" this is called Fminor.

Key Root 2nd 3rd 4th 5th 6th 7th

A-min A B C D E F G

E-min E F# G A B C D

B-min B C# D E F# G A

F#-min F# G# A B C# D E

C#-min C# D# E F# G# A B

D#- Eb- D#/Eb E#/F F#/Gb G#/Ab A#/Bb B/Cb C#/Db

Bb-min Bb C Db Eb F Gb Ab

F-min F G Ab Bb C Db Eb

C-min C D Eb F G Ab Bb

G-min G A Bb C D Eb F

D-min D E F G A Bb C

A semitone (or half step) is the smallest increment on a western musical instrument. On a piano, it is represented by moving from one key to the next, and on a guitar, it is represented by moving from one fret to the next. As an example, on a piano, moving from middle C to the black key directly next to it on the right, we would get a C# would be a semitone. Moving from middle C to the next WHITE key on the right, which is the D, would be a tone from the middle C (also known as two semitones or a whole step). On a guitar, moving from the open A string to the first fret on the A string A# would be a semitone, whilst moving from the open A string to the second fret B would be a tone (two semitones).

Major Again

So if we look at the C Major scale, it looks like this:

C (root note)

Then up a TONE to D

Then up a TONE to E

Then up a SEMITONE to F

Then up a TONE to G

Then up a TONE to A

Then up a TONE to B

And finally up a SEMITONE again to finish back on C.

All major keys follow this pattern, and you can start a Major scale on any note.

A couple of things to be aware of: Some notes have the same sound, but different names depending on which KEY they are in. For example, an A# is the same note as a Bb as if you move up ONE semitone from A it becomes A# and if you move down ONE semitone from B it becomes a Bb. Again, you don’t need to worry too much about this if it’s confusing you as we’re going to stick mainly to simple chords and keys.

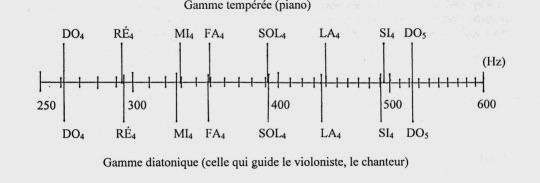

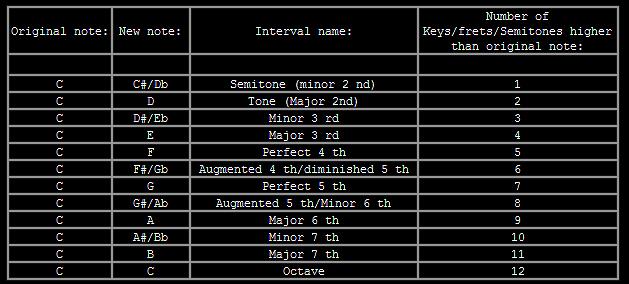

Intervals and Chords.

Basically each note and the following note is half a step. From the first note to the next nearest note is half a step (the same) and is called a semitone. On a piano this is each following key. On a guitar this is each following fret.

Timeline.

The purpose of a time signature is to show you what type of feel, rhythm, and speed you should play certain notes, phrases and bars. There are various time signatures in music. The two most common are Four-Four time, and Three- Four time. The first number in the time signature denotes the NUMBER of notes you will be playing, PER BAR and the second number tells you what TYPE of note you’ll be playing. So if we’re playing in Four-Four time, you would have four even beats of quarter notes, and count like this: One, Two, Three, Four, One, Two Three, Four etc. If you were playing in three four time, you’d be using the same length notes, but only count three of them per bar, for example: One, Two, Three, One, Two, Three etc. The following are the most common types of note found in Western music, and each of these notes also has a corresponding rest that has the same duration. These are also found on the examples below.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

C D E F G A B

C# D# F F# G# A# C

D E F# G A B C#

D# F G G# A# C D

E F# G# A B C# D#

F G A A# C D E

F# G# A# B C# D# F

G A B C D E F#

G# A# C C# D# F G

A B C# D E F# G#

A# C D D# F G A

B C# D# E F# G# A#

Ionian: No Change

Dorian: 3b,7b

Locrian: 2,3,5,6,7b

Lydian: 5b

Phyrgian: 2,3,6,7b

Mixolydian: 7b

Aeolian: 3,6,7b

Major: 1,3,5

Sus2: 1,2,5

Minor7th: 1,3b,5,7b

Minor: 1,3b,5

Sus4: 1,4,5

Major7th: 1,3,5,7

Add2: 1,2,3,5

Fifth: 1,5

Diminished: 1,3b,5b

Scales

Major pentatonic c d e g a

Neapolitan minor C Db Eb F G Ab B C

Hemitonic pent3 C D Eb G B Spooky

Pent var C E G A Bb Smooth

C-majdom7 C E G B yawm, a major scale

c-mindom7 C Eb G Bb minor

Harmonic mindom7 C Eb G B phantom minor

Melodic mindom7 C Eb F A Really F-majdim7,2nd

Esoteric 6th Cb D F A Dreams ?

Augmented C E G# Tence

Diminished C Eb Gb Also Tence

Minor 3rds C Eb Gb A Tence , dreamy

Harmonic minor C D Eb F G Ab B Sad

Melodic minor C D Eb F G A B Nice sweat

Whole tone C D E F# G# A# Whoa tripping!

Augmented C D# E F# G# B# nasty tension

diminished C D Eb F Gb Ab B Sad Ab+B = Bbb/Cbb

Enigmatic C Db E F# G# A# B Indeed very strange

Bizantine (gypsy) C Db E F# G# A# B Spooky

Locrian (arabian) C D E F Gb Ab Bb Drunk

Persian C Db E F G A# B Secrets

Spanish 8 tone C C# D# E F F# G# A# Ummm

Native American C D E F# A B Bold btw which tribe

Major bebop C D E F G Ab A B Funky min/maj

Barber shop1 C D E F G B D F G B Full

Barber shop2 C G C E G B Same as 1 but sad

Rain A# D E F# G# C D F# G# Messed pissed off

Crystalline min9#7 C G B Eb G D Eb Bb D

Gb Bb F Gb Db F A Very mad as hell

Popular blues C D# F F# G A# pissed crunchy

Blues II C D# E G Ab D# G Spacy dissonant

Total disharmony C Db E F G Ab B C D Eb

F# G A Bb C# D# Ouch thunder

Sus2 C D G Cool nine

C-phuq'd C F Ab Bb

Db-grace major C F Ab Db F G Db Gb

E-blues C D E G Ab Gb Db F

Neaplotitan major C Db Eb F G A B C

Oriental C Db E F Gb A Bb C

Double harmonic C Db E F G Ab B C

Enigmatic C Db E F# G# A# B C

Hirajoshi A B C E F A

Kumoi E F A B C E

Iwato B C E F A B

Hindu C D E F G Ab Bb C

Pelog C Db Eb G Bb C

Gypsy C D Eb F# G Ab Bb C

Maj phrygian C D F E F G Ab Bb C

Maj locrian C D E F Gb Ab Bb C

Lydian min C D E F# G Ab Bb C

Overtone C D E F# G A Bb C

Arabian C D E F Gb Ab Bb C

balinese C Db Eb G Ab C

Gypsy C Db E F G Ab B C

Mohammeddan C D Eb F G Ab B C

Javanese C Db Eb F G A Bb C

Persian C Db E F Gb Ab B C

Algerian C D Eb F G Ab B C D Eb F

Aeolian C D Eb F G Ab Bb C

byzantine C Db E F G Ab B C

Hawaian C D Eb F G A B C

Jewish E F G# A B C D E

Mongolian C D E G A C

Ethiopian G A Bb (b) C D Eb (e) F (F#) G

Spanish C Db E F G Ab Bb C

Egyptian C D F G Bb C

Japanese C Db F G Ab C

Chinese F G A C D F C E F# G B C

New pentatonic C D E F# A

jap penta C Db F G Ab

Bal penta C Db F Gb A freaky = Db-maj7dim4?

Pelog penta C Db Eb G Bb dreamy

Musical Definitions, Terms relating to TEMPO.

GRAVE - Very slow and solemn

LARGO - Very slow and broad, with dignity

LENT or LENTO - Very slow

ADAGIO - Very slow and expressive

LARGHETTO - Not as slow as LARGO, but slower than ANDANTE

ANDANTE - Rather slow, but with a flowing movement ("Walking tempo")

ANDANTINO - A little quicker than ANDANTE

MODERATO - Moderate speed- not fast, not slow

ALLEGRETTO - Light and cheerful, but not as fast as ALLEGRO

ALLEGRO - Merry, quick, lively, bright

VIVO - Lively, brisk (usually with ALLEGRO, as ALLEGRO VIVO

VIVACE -Vivacious, faster than ALLEGRO

PRESTO -Very quick, faster than VIVACE

ACCELERANDO - Abbreviated: accel. To increase the speed gradually

STRINGENDO - Abbreviated: string. To increase intensity by increasing tempo

AFFRETTANDO - To increase the speed gradually

ALLARGANDO - Abbreviated: allarg. Slower and louder

RITARDANDO - Abbreviated: Ritard. or Rit. Gradually slackening the speed.

RALLENTANDO - Abbreviated: Rall. Slowing down, gradually.

RUBATO - Literally means "Robbed"- a lingering on some notes and hurrying of others; free from strict tempo, but preserving the value of the rhythmic notation.

A TEMPO - Return to original tempo after a RITARD

TEMPO I (PRIMO) - Return to original tempo after a RITARD

Words that often accompany TEMPO Markings:

MOLTO -Very much. MOLTO RITARD means to slow down exceedingly

MENO - Less. E.g., MENO MOSSO means less fast (slower)

PIU - More

NON TROPPO - Not too much, e.g., ALLEGRO NON TROPPO means fast, but not too fast

POCO A POCO - literally "little by little". Used in combination with tempo markings. e.g., ACCEL. POCO A POCO means to increase the speed gradually over a span of measures.

Terms relating to DYNAMICS (from soft to loud):

PIANISSIMO -(abbr: pp). Very soft

PIANO - (abbr: p). Soft

MEZZO - Medium or moderately

MEZZO PIANO - (abbr: mp). Medium soft

MEZZO FORTE - (abbr: mf). Moderately loud

FORTE - (abbr: f). Loud

FORTISSIMO - (abbr: ff) Very loud

DIMINUENDO - (abbr: dim.) or the sign means gradually getting softer

CRESCENDO - (abbr: cresc.) or the sign means gradually getting louder

POCO A POCO - Little by little. Indicates a gradual increase or decrease in volume of sound.

ACCENT - A stress on notes so marked

SFORZANDO - (abbr: sfz) A strongly accented note or chord

SFORZATO - (abbr: sfp) strongly accented by then immediately PIANO

SUBITO - Suddenly. Usually to indicate a dramatically sudden change in dynamic level of sound.

AGITATO - With agitation- excitedly

ALLA - In the style of (always used with other words).

CON - With (as a connecting word), e.g., ANDANTE CON AMORE- slowly, with tenderness

ANIMATO - With animation, in a spirited manner

APPASSIONATO - With intensity and depth of feeling

BRILLANTE - Bright, sparkling, brilliant

BRIO - Vigor, spirit

CANTABILE - In a singing style

DOLCE - Sweetly and softly

ENERGICO, CON - With expression

FUOCO, CON - With fire or much energy

GRANDIOSO - In a noble, elevated style

GRAZIA, CON - With a graceful, flowing style

LEGATO - Smooth and connected, in a flowing manner (Opposite of STACCATO)

MAESTOSO - With majesty and grandeur

MARCATO - In a marked and emphatic style

PESANTE - Heavily, every note with marked emphasis

QUASI - In the manner of; e.g., QUASI UNA FANTASIA- in the style of a fantasia

SCHERZANDO - In a light playful and sportive manner

SCHERZO - A jest, one of the movements of certain symphonies, a composition of light and playful character

SECCO - Dry, plain, without ornamentation

SEMPRE - Always; e.g., SEMPRE STACCATO- to continue playing in a short and detached style

SPIRITO, CON - With spirit, or animation

STACCATO - Short and detached, with distinct precision (the opposite of LEGATO)

TENUTO - Sustained for the full time-value

TRANQUILLO - With tranquility, quietly, restfully

LARGO MA NON TROPPO - Slow, but not too slow (ma = but)

ADAGIO CANTABILE E SOSTENUTO - ('e' = and) Very slow and in a sustained and singing style

ANDANTINO, CON AFFETUOSO - Faster than ANDANTE, with tender feeling

ALLEGRETTO CON GRAZIA - A moving tempo with a graceful flowing style

ALLEGRO AGITATO - Quick with agitation

POCO PIU MOSSO - A little quicker

ALLEGRO CON MOLTO SPIRITO - Fast with much spirit

ANDANTE MAESTOSO - Rather slow-moving tempo, majestic feeling

PRESTO CON LEGGIEREZZA - Very fast with lightness and delicacy

ACCIDENTALS - Flats and double flats, naturals, sharps and double sharps

ALLA BREVE - Cut time. The half-note is the unit of the meter

ARPEGGIO - A broken chord (Each note of the chord played in succession)

ATTACCA - Begin the next movement immediately

CADENCE - The close or ending of a phrase

CADENZA - An elaborate solo passage with fancy embellishments to display the proficiency of a performer.

CHROMATIC - Proceeding by semitones

CODA - Literally "A tail"- the closing measures of a piece of music

CON - With; e.g., CON SORDINO means "with mute"

DA CAPO - (abbr: D.C.) from the beginning

DAL SEGNO - (abbr: D.S.) to the sign

DIVISI - Divided, one performer plays the upper notes, the other plays the lower notes

FERMATA - A pause, marked

FINE - The end

G.P. - General Pause; a dramatic moment of silence for the entire ensemble

SEGUE - To the next piece without pause

SENZA - Without; e.g., SENZA SORDINO means without mute

SORDINO - A mute (used by brass and string players)

TACET - Be silent

TEMPO PRIMO - (Sometimes TEMPO I), means to return to the original tempo after a RITARD or ACCEL.

V.S. - Abbreviation found at the lower right corner of a music page and means to turn the page quickly.

COL LEGNO - Applies to string instruments.

GLISSANDO - To slide. Pulling or drawing the finger quickly up or down a series of adjacent notes. Also poss. on trombone and other inst..

That is all for now...

Denis van der Velde

AAMS Auto Audio Mastering System

www.curioza.com

Recording

Welcome to the infomation page about recording music.

Recording Music

The art of recording music is filled with information that is mostly technical. There is loads of information on miking techniques, what microphones and preamps to use, and how to process them. What is less often talked about are the fundamentals that underlie those techniques and choices. The acoustics of the recording space and the quality of the musician will define the sound of the recording more than any mic technique or processing chain ever will. Behind the techniques lies the real foundation of making great recordings. It's the information you don't often get because most are not keenly aware of its existence. Many have only worked in professionally treated acoustic spaces designed for recording and can often forget that their audience is not working in the same conditions. Many work through the problems that arise with intuition rather than taking the time to really understand what lies underneath all the technical choices they make. In reality, it usually takes years to become great at recording music. During that time, allegiances to different pieces of gear will come and go and solutions will be based mostly on experience. When problems arise, it is often easier to blame the studio, available mic selection, recording console or the recording space. If you want to make great recordings, regardless of the recording space and equipment you are working with, you will have to learn something that is more fundamental. Essentially, no two recording situations are identical and each requires a discerning ear and eye. Most of the great engineers learned by experience, trial and error, and working under great engineers before them that understood how sound works. They learned how to use acoustics to their favor, and learned how to work with musicians to get the best performances out of them.

The 3 Types of Recording

In this article I will break down the art of recording music to its most basic elements. The articles that follow in the links at the bottom of the page will get into details about recording specific instruments and the best way to manage those recording situations

Essentially you can break down the types of recording into 3 basic categories:

1. Acoustic Recordings

2. Electronic Recordings

3. In the Box Recordings

Even though, electronic and in the box recordings are not dependent on the acoustic space, the principles of acoustics are still very much at play because that is the only way we know how to perceive sound. Let's take a closer look at each:

Acoustic Recordings

Recording music in the acoustic realm is all about capturing sound waves through microphones and converting them into an electronic signal so they can be captured and recorded. Today, those recordings are mostly into computers and onto hard drives. Whether you are recording analog or digital, the basic process hasn't really changed a whole lot of over the last century or so. Music, for the vast majority of its history to humankind, has always been acoustic. It is only in recent decades that music has gone to purely electronic sources.

The concept of recording, came into play in late 1800s with the inventions of Thomas Edison. Music recording soon followed, although the capabilities were very limited. Primarily, all recording was acoustic material. The technical issues of capturing music in recorded form have undergone immense development over the last 100 years or so. In years past, the mechanical limitations of recording devices limited the engineer's options. Today, those options are seemingly endless. The irony is that the greater number of options available today have taken many engineers away from the fundamentals of acoustics and focused them on new gear and plugins instead. As the quality of recording technology increased, so too did the importance of the acoustic recording space. The decisions made about how to manage the recording space became critical to the quality of a music recording. If you want to achieve a very big live drum sound, you are not going to get it by recording in a small dry space. In the end, no mic will make a recording space sound bigger than it is.

Managing Acoustics

When you place an instrument in a recording environment, that instrument will sound different, sometimes radically different, depending upon how and where you place it in the room. This is especially important for recording music in spaces that are smaller than 20 x 20 feet. There is no microphone that will solve all of the problems with a bad acoustic environment. Even with the best gear all you will get is a very accurate recording of very limited acoustic environment. This does not mean you have to spend thousands of dollars on acoustic treatments. Even professionally treated recording studio environments require careful placement and attention. The most important thing, in any recording situation, is to listen carefully as you move the instrument around room. Find a place in the room that enhances the sound of the instrument without making it sound unnatural. Acoustics is really the key to capturing great recordings and is often overlooked by most novice engineers. If you just dump an instrument anywhere in the room and throw a mic in front of it, you are basically rolling the dice and hoping that a good sound comes up. If you're a bit more conscious about how you place an instrument in a recording space, then you will get significantly better results, with much less effort, and be much happier in the end, even if you are using inexpensive recording equipment. How you choose the right acoustic environment, and how you treat the immediate space around the instrument is unique to each instrument and the sound you are trying to achieve. These guidelines and methods will be covered with more detail in the individual recording instrument links at the bottom of the page.

Electronic Recording

The second method of recording music is electronic recording. Electronic recordings go back to the invention of keyboards and synthesizers, and also with basses and guitars. The idea of using a direct electrical signal is that you are bypassing the acoustics altogether. For many instruments like bass and guitar, the amplifier is a huge part of the sound you are trying to create. Without the speakers and acoustic environment, you have to count on the electronics you are using to create the sound for you. The typical method for capturing electronic audio is through a DI box. The DI box will take any signal that comes from a high impedance unbalanced source, like from a guitar or bass and convert it into a balanced signal so it can be plugged into a mic preamp and recorded. The balanced lines help to keep the signal quiet with a minimum of degradation. Long guitar cables will pick up loads of noise and you can end up with significant signal degradation. Always keep unbalanced cables to a minimum in terms of their length. When recording music with keyboards, you are dealing with electronics that are controlling oscillators to generate synthesized sounds that are sometimes meant to emulate acoustic instruments. The older ones are typically connected to a DI although many of them now have balanced line level outputs. This allows them to be brought directly into a line level input in a recording console. They can then be recorded without having to add a significant amount of gain, thus keeping noise to a minimum. The only issues from a technical perspective are selecting the sounds and editing them until you get it to sound the way you like. If it is a bass, you will need to change pickups, adjust the tome knobs or switch between picks or fingering methods to get the sound you're looking for. Many direct boxes, designed for bass, have pre-amplification stages that include distortion equalization and tube components that allow you to add some character. The same can be done with guitar using pedals and effects to add warmth and depth to the sound before gets recorded. Otherwise, the only other issues that you are making sure the signal passes cleanly, is full frequency, and that there are no buzzes, hums or noises. Most DI boxes have ground lift switches that help to eliminate these problems.

In the Box Recording

The third method of recording music is in the box recording. In the box recordings are primarily referencing to computer recordings where all of the recording work is done inside the actual recording application. There is no audio coming in externally into the recording device. Recording music inside the box is most often, or at least to some degree, MIDI recording. Essentially, you are capturing the technical aspects of a performance through a midi keyboard or other midi instrument. Once you have captured the performance, you have the ability to grab any sound from the vast number of software synths and sample libraries available and edit them till you get the sound you want. A performance played with a flute sound, can easily be changed or adapted to be a clarinet or oboe sound. This, of course, is not possible with acoustic recordings. The art of this types of recording lays in the ability to make these artificially generated sounds seem like the real thing. When recording music in the box what you are actually recording is MIDI control signals, not the actual audio. This allows you to edit your performance, fix wrong notes or sloppy passages. You can also change the dynamics if you play a note too loud or soft by adjusting the velocity. You can change the length or sustain of notes and countless other parameters until you to get exactly the performance you desire. When dealing with loops, you may be dealing with audio loops or MIDI loops. Audio loops are essentially acoustic recordings or electronic ones that are premixed and effected. You will have limited control in affecting audio loops, which is why the libraries are typically so vast. MIDI loops, by contrast, can be edited and manipulated in exactly the same way that any MIDI performance can including quantization and sound selection.

Moving On

All these methods for recording music are still primarily about capturing performances. To make great recordings, the goal must always be to capture great performances. Great performances will transcend the recording techniques used. Sometimes a low fi recording captures the essence of a performance better than a squeaky clean full frequency one will. Playing with this concept, is truly the art of recording music. Select from the list below for the detailed recording techniques of specific instruments.

RECORDING VOCALS PART 1

The lead vocal is typically the most important part of any song. As a result, recording vocals almost always requires the most attention to the details of performance and sound. Capturing a great performance is a byproduct of preparation, a good recording setup and great communications skills. Because the vocal is the primary focus of most music productions its importance cannot be overstated. The following tips should help to make the process of recording vocals less stressful. To capture a great performance requires as much attention from the producer and engineer as it does the artist.

The 2 Aspects Of Recording Vocals

There are 2 basic aspects to recording vocals. The technical aspect and the emotional and psychological aspect. The technical aspect of vocal recording is simple once you understand the basics principles of audio that most fundamentally affect the sound quality of a recording. These basic principles will help you to make great recordings regardless of the quality of the gear you are using. They set the foundation for all the other techniques and tricks you use. The second aspect of recording vocals is the emotional and psychological aspect. You need to make the performer feel comfortable and confident in what they are doing. This process is supported by creating the space from which they can perform well. The recording studio is a very unnatural environment, and most people don't perform well without some level of inspiration. Many feed off the excitement of an audience or the energy of a live performance with a band. The recording studio, however, is a completely different experience. Careful planning of the technical and psychological aspects of recording vocals is absolutely necessary to get the best performance possible.

The Technical Side of Recording Vocals

The technical aspects of vocal recording often get the most attention in engineering circles, and for good reason. The ability to hear subtle inflections in a performance and the ability to clearly understand the lyric and melody go a long way to adding to the listener's experience. Unfortunately, this is not the whole solution to getting great performances. Discretion must be used when applying the techniques that give you a great 'sound' so as not to put the performer in an uncomfortable position. Ultimately, it is their performance that will make people want to listen, not the quality of the recording. The following sections will break down the technical aspects that make great quality recordings while being sensitive to the needs of the artist. If you ignore this simple principle, you may end up with a great 'sounding' recording that nobody wants to listen to.

Selecting The Best Space To Record

The most important decision to make when recording vocals is selecting the right space to record in. Selecting a space that best supports the sound of the vocal while giving the artist a comfortable space to perform requires some careful attention.

Most people do not listen carefully enough to the sound of the space unless it is doing something obviously wrong. Each person has a unique voice with a unique tonal quality. No one space will work perfectly for every artist and for every song. The decisions made here affect every other level of the recording chain, for better or for worse.

What To Look For

In a professional recording studio, most engineers will record vocals in the biggest space available. The reason has nothing to do with the reverb but rather with way the early reflections will affect the tonal quality of the voice. What happens in every recording space is that sound will travel in all directions from the sound source. The direct sound wave does not stop at the microphone, it continues past it and bounces off all the surfaces. Depending on the shape of the room and the acoustic treatments, the sound will return to the sound source and mic a short time later. How long it takes to get back is critical. If it comes back within 20 milliseconds (ms) it will merge with the original signal and tonally color the sound of the voice. This is important to understand because this will greatly affect the tonal quality of the voice. It can make any voice sound hollow, bright, muddy, clouded or harsh no matter what mic you use.

A Little Math

It all starts with the speed of sound and the distance it has to travel. The rest is simple math. Sound travels at 1130 ft. per second or 344 meters per second. This amounts to .88 ms per foot or 3 ms per meter.

To get past the 20 ms delay time, you must be at least 12 ft. or 3.5 meters away from any surface. The reason for this is that the sound must travel to the surface first before coming back to the mic. The total length of travel from the sound source will determine the delay time. Because of gravity, the reflections from the floor are mostly beyond your control. They will always create a delay within 20 ms. Most engineers use rugs to help limit this transmission. The rest of the surfaces will require a bit more attention. In a large recording space this is not an issue. In a small recording space, it can be a big one. The knee-jerk reaction is to completely deaden the space with foam or absorptive materials, but this is not a truly effective solution. This will create an unnatural balance of low to low mid frequencies that are the bigger source of the problem.

Get Out Of The Closet

I am not a big fan of recording in small spaces. I find they rarely, if ever work, and are largely uncomfortable claustrophobic spaces. Not exactly the best environment to perform in for most artists. From a technical point of view, very small recording spaces create enormous problems that far outweigh the convenience. Surfaces too close to the source signal will create an enormous amount of resonant constructive interference in the low mid frequency range. The result is often a boomy, muddy or flat sound that is unbalanced and unnatural sounding. Covering the surfaces entirely with foam will only serve to further cause imbalances in the frequency response. It's not the deadness of a space that creates the sense of dryness or immediacy. It is the balance of dry to reflected energy that creates that sense. Without the reflected energy in the sound the sense of space is entirely lost and the dry signal flattens out and loses its sense of aliveness. There is a reason nobody records in anechoic chambers. It's important to understand the difference between tonal coloration and frequency response. Tonal coloration comes from reflections that return to the source within 20 ms. Signals this close in time get merged together by our brain. This process is called temporal fusion. Once these tonal imbalances are recorded, they cannot be removed with EQ.

How To Record Vocals In A Small Room

Just because small rooms are not ideal recording spaces doesn't mean that you can't get great results. There are many ways to control the effect of early reflections without sucking all of the energy out of a room. While some of this will involve acoustic treatments, the process starts with something more fundamental. The first step in getting a great sound involves finding the best placement for the vocal. Start by having the vocalist sing the song as you walk around the recording space. If you have more than one space to work with, walk through them all until you find the best sound. Try to focus on the tonal quality of the voice and not the reverberant energy of the room. Notice if the tone becomes boomy, hollow or thin sounding. As you walk around the space take note of where the voice sounds most balanced and natural. This is the best place to start.

Treating The Space

The standard procedure for recording vocals in a professional recording studio is to build a semicircular booth around the vocalist in the biggest room. The booth is created by using gobos. A gobo is a freestanding acoustic baffle that can be easily moved around a room. The ones used for vocals stand at least 6 feet tall. The booth should be large enough to allow freedom of movement by the artist without creating a claustrophobic feeling. A rug is usually set on the floor inside the booth area. In addition to absorbing reflections from the floor it also serves to minimize noise from shoes and vibrational energy transmitting through the stand to the mic. The reason this works is that it minimizes the effect of tonal coloration from the early reflections (less than 20 ms) and also minimizes the reverberant energy from getting into the microphone. It's important to note that it doesn't eliminate them, just minimizes their effect. With a little resourcefulness, a very similar approach can be used in the home recording environment. Suspending heavy packing blankets from the ceiling around the recording area can achieve a similar effect. The difference between this approach and layering the walls with foam is that the sound will get absorbed from both directions. Leaving the booth and returning to it after reflecting off the wall. Layering the walls with foam does not minimize the early reflections nearly as well as the booth and it kills all of the higher frequency reflections that make a recording sound alive and present. By allowing those frequencies to propagate around the outside of the booth, a subtle sense of presence will be added to the vocal recording.

Selecting a Mic

Selecting a mic is the next step in getting a great vocal sound. No mic will undo a poor recording space, but once you have established the best recording space, the mic selection will take your sound to the next level. Microphones are like gloves. There is no one glove that fits everybody perfectly. There are some microphones that are exceptionally good at capturing most people's voices, but every person's voice is still unique. Unless you happen to own one of these very rare microphones, it must be selected uniquely for each person. I've always found the best results were gained by setting up as many microphones as I felt might work for the voice I was going to record. Aside from the time it takes to set up the microphones, it doesn't actually take a lot of time to pick one.

How to Pick the Best Mic

Start by recording a vocal line with each mic. The vocalist should sing a line or two from the song that you're going to be recording. One of the mics will to stand out beyond the others in terms of imaging and tonal quality. If there is a significant change in the vocal range later in the song, it may be worth recording that as well to make sure the mic can maintain the sound. It is typical that tube mics and condenser mics are selected most often for recording vocals because they give the most clarity. With voices that are very bright, a dynamic mic can also come in very handy. Dynamic mics can cut away some of the harshness of a voice and add some warmth and body when needed. It important not to rule out a mic because of its type or price tag. The most important part of recording vocals is getting the sound you're looking for no matter how you have to get it. If you need to, make the test blind so that you are not swayed by preconceived notions of quality.

Pop Filters

One of the many technical issues with recording vocals is plosives. A plosive is puff of air that is sometimes emanated by the vocalist when singing words that contain the letter P. This puff of air can strike the diaphragm of the microphone with enough force that it causes a low frequency pop or distortion. A pop filter, or pop screen, can be used to break up the puff of air while still allowing the sound to pass through to the microphone. If you don't have a pop filter handy, another way of getting rid of plosives is by taping a sharpie to the front of the microphone. It should go right down the center of the diaphragm. The sharpie will spread the air out around the diaphragm without really affecting the frequency response. Pop filters can serve a second valuable purpose even if there's not a big plosive problem with your vocalist. A pop filter also allows you to set a distance from the microphone to which the vocalist can easily and consistently return. It is very important to keep a vocalist singing at an even distance from the microphone. The distance is important for creating a consistency in terms of frequency response and tonal characteristic. If the vocalist is pulling away or moving around or turning their head when singing then will not be singing directly into the diaphragm. The result is variations in the tonal quality of the voice.

Mic Placement

The real issue with microphone placement for recording vocals is a matter of comfort for the vocalist. If the microphone setup feels obstructive to the vocalist it will take way from their performance. Doing everything possible to make the artist comfortable will always yield the best results. The primary focus of your setup will be to make sure that the vocalist is able to perform comfortably with good posture. The professional method of recording vocals involves the use of a big boom stand. The boom stand is set up out of the way to the left or right of the vocalist. The boom stand extends above the head of the vocalist and drops the mic from above down in front of the mouth of the vocalist. This typically works very well because it keeps the microphone out of the way and allows the vocalist to maintain good posture. As a general rule, the artist should never be seated when recording vocals. If standing is a problem for the artist, then the next best option is to use a stool. This way, they are at least mostly standing up. This can also be handy if you have a long session planned and want to keep the vocalist fresh.

Lyric Sheets

There is one issue that often arises when the microphone is coming from above the head of the vocalist. If the vocalist needs to look at a lyric sheet, the microphone is directly in the way of their sight line. What happens is that the lyrics will either be placed to the left of the right of the microphone. This naturally leads the vocalist to turn away from the mic and not directly into it when they look at the lyrics. There are 2 ways to deal with this issue when recording vocals using lyric sheets. One way is to set up a mic stand so the microphone can be flipped upside down and come up from below the head, not above. This way they can look straight over the top of the microphone to see the lyrics. As the singer looks at the lyrics they are actually leaning into the microphone not looking away from it. The pop screen will help to keep them at the exact distance you want them to be from the front of the microphone. Sometimes it is best to set up a vocal mic coming from the side if you have a quality heavy duty mic stand that can handle the weight of a good microphone. The benefit of this setup comes when using tube mics. The tubes will generate heat that naturally goes up towards the diaphragm if set upside down as in the previous example. This can negatively affect the quality of the sound because the diaphragm will be heated and expand thus changing its performance characteristics. Using a side position will allow the vocalist to see the lyrics and sing directly into the microphone while also keeping the heat from affecting the sound.

Mic Settings

There may be a series of options on your vocal microphone that will help control the sound quality when recording vocals. These options vary from mic to mic, but here is a list of the most common ones found on quality vocal mics.

• Polar Pattern

• Filters (EQ)

• Pads

Polar Pattern:

The polar pattern of a microphone determines the direction from which the microphone is most sensitive to sound sources. The selection of the polar pattern will also determine from what direction, if any, the mic will reject signals. When recording a single vocalist, the pattern is typically set to cardiod. The cardio pattern will, to greater or lesser degrees, reject signals from all directions except from directly in front of the mic. This polar pattern is most suitable for recording a single vocalist. When recording two vocalists with at the same time one mic, a figure 8 pattern will allow equal sensitivity from both the front and back of the mic while rejecting sounds from the sides. This pattern makes recording more comfortable because they do not have to crowd around the front of the mic. When recording a group of vocalists through one mic, it is typical that the omnidirectional polar pattern is selected. the selection of Omni enables equal sensitivity from all directions. This allows the vocalists to comfortably sing toward the mic from every direction.

Filters (EQ):

Filters are a very powerful equalization tool used to eliminate problematic frequencies that are not a necessary part of the sound source. There are 3 basic types of filters, High Pass, Low Pass and Notch. While all three types are helpful, only the high pass filter type is used for recording vocals. It is the only type you will typically find on a mic. Many large diaphragm microphones use a High Pass (low cut) filter because of their increased sensitivity to low frequencies. This allows the engineer to dramatically remove low frequency rumble that can be caused by air conditioning systems and poor acoustic isolation. Some have selectable frequencies but most are fixed to a single frequency below which signals are cut. The quality of these filters vary with the quality of the mic and it is common for many mic preamps and audio interfaces to include a High Pass (low cut) filter. Check to see which sounds best without affecting the quality of the vocal recording. If the low frequency rumble in a room is excessive, it may be necessary to use both if there is no way to eliminate the source of the rumble.

Pads:

A pad allows the electronics of the microphone to be buffered from sound sources that create high sound pressure levels. This does not necessarily mean that you won't get distortion as the diaphragm of the mic may not be able to handle the excessive sound pressure levels. If this is the case the mic will need to moved farther from the sound source. For most vocalists a pad is not necessary, and it is often better to back the vocalist away from the mic if they project too loudly. This is a very common practice when recording opera singers that are trained to project with enough power to fill an opera house.

Controlling Dynamics

Headphones

Although the headphones are technically on the performers side of the recording, their control is almost always the dominion of the engineer. Here are some tips that will help to make your headphone mixes best for recording vocals. The best place to start is by using the best quality headphones you can find. You want to avoid "open back" headphones because they are vented and the sound will bleed into the mic. Make sure you have a good cleanly amplified signal with no distortion. When preparing a mix for the artist, try to make the mix as dynamic and alive sounding as possible. The mix should be exciting so that the artist can feed off the energy of the song the same way they would in a live performance. Be very attentive to how the artist feels about the mix. Make sure they are able to hear themselves clearly and cleanly. I generally try to avoid using reverbs when recording vocals because it makes it harder to hear pitch accurately. If the headphone mix does not feel right to the artist without reverb, then add in just as much as is needed to add the presence they need to perform well. Try to avoid long washy reverbs if possible. If the artist is having problems with pitch using headphones, have them take one headphone off so they can tune acoustically. This is a very common solution to solve pitch problems when using headphones. Create a mono mix and cut signal to the unused headphone so that it doesn't bleed into the mic.

Controlling Dynamics Acoustically

There are many different thoughts about how to best control dynamics of a vocalist in the recording room. It is typical that the artist will sing louder in different sections of the song if the melody takes them to the power range of their voice. Most vocalists will pull away from the microphone when these parts arise. While this is very dramatic looking in concert it is not always great for recording vocals. Generally, I would rather have them at an even distance from the mic throughout the performance if possible. If the artist will give me a better performance because they don't have to think about staying in one position, I will deal with the sound later. Always take a quality performance over a quality sound if there's no way to get both. A well trained vocalist with good technique will not necessarily sing louder when going to the power range of their voice. Unfortunately, this is the exception rather than the rule and you will have to deal with these issues as part of the recording process. Never force an artist to think about technique when recording vocals. It is always better to work out the technical issues of a performance in a rehearsal session so that the focus is entirely on expression and feeling in the recording session.

Mic Preamps

Selecting the best quality mic preamp is the next stage of the vocal chain. A good mic preamp will have loads of headroom and will not distort if the vocalist belts away. Compare as many mic preamps as you have available to find the one that best suits the vocalist.

Always leave yourself a good bit of headroom, especially with very dynamic performers. You can always make up again at a later stage in the recording chain, but you will not be able to get rid of the distortion. If the gain is too high for your mic pre, you may need to use a pad. Most mic preamps have a pad, but make sure you compare the quality to the one on the microphone to see which sounds best. If necessary, you can ride the mic preamp gain during the performance to help even out the gain. Make every attempt to eliminate distortion at every phase of the recording chain. Be careful to monitor the gain as the voice starts to open up. Usually, a vocalist will not sing with full power until they are warmed up and singing the song full force. Be prepared...

Compression and EQ

If all of the previous details have been considered and brought into focus, what happens with the EQ and Compression should be a breeze. There are many thoughts regarding what the processing order should be after the mic preamp. Here is my general view:

EQ Before Compression

Subtractive EQ is best before compression, additive EQ is typically best after the compression. The reason for this is simple, subtractive EQ is meant to eliminate noise that you don't want. If you don't get rid of this noise before compressing then the compressor will make the noise louder and it will be harder to remove later. The most typical form of subtractive EQ is a high pass or low cut filter. The purpose of this filter is to roll off low frequency rumble or noise that is below the frequency range of the voice. Many vocal mics have this filter built into a switch. It is also common to find a filter stage built into the mic pre. Make sure that when the filter is engaged, it does not roll off frequencies from the low end of the voice. You may need to check the specifications of the owner’s manual to verify the frequencies if it is not labeled on the mic or preamp.

EQ After Compression

EQ after compression is typically additive. If you have followed all of the techniques in the prior 2 articles leading up to this point, you should need very little if any EQ. If the recording setup is too limited to accommodate all of the techniques outlined in the previous articles, then some EQ may be necessary to make up for what is missing. More on this later in Recording Vocals part 4.

Compression

Generally, most engineers agree that compression, when recording vocals, should be as transparent as possible. You don't really want hear the compression you just want to control the dynamic of the vocal. There are many ways to approach doing this, let's take a look at a few.

One Compressor Approach